“One of the biggest strengths of this campaign was that it was not centered around a single identity. It was built as a citizen’s device where the victory would also belong to the citizens.”— Emma Avilés Thurlow

Background

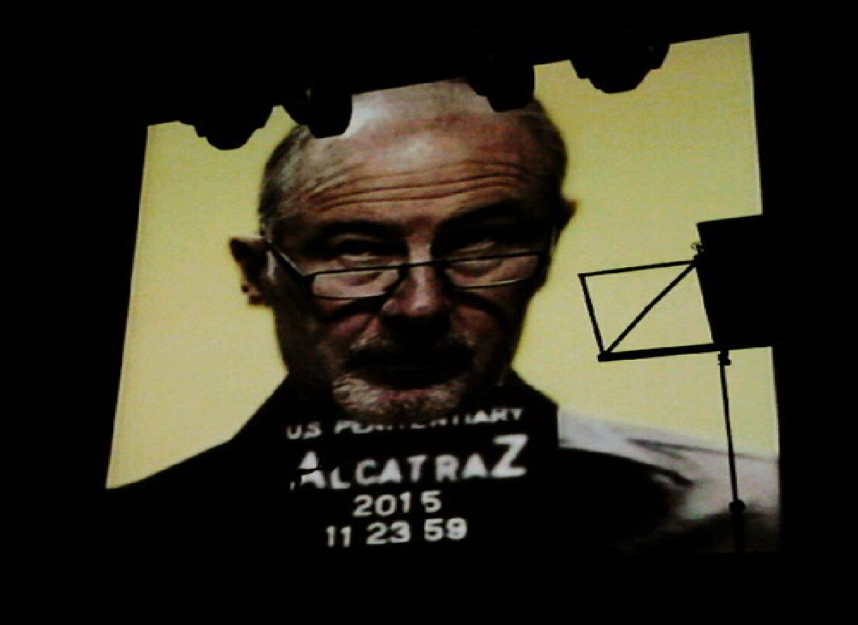

In one of Spain’s most high-profile cases, a group of activists successfully sent Rodrigo Rato, the ex-Minister of Economy, ex-President of Bankia and formerly expectant Prime Minister of Spain, to jail for corruption. Alongside him, 64 other bankers and politicians were also sentenced to varying terms of imprisonment.

The convictions were the result of a lawsuit filed by an anonymous collective called 15MpaRato against the executives of Caja Madrid, Spain’s oldest savings bank, which later merged with six other savings banks to form Bankia. The lawsuit brought to light how the corrupt bankers had defrauded over two billion dollars from three hundred thousand small investors through forgery, manipulation of documents and misleading advertisements.

In the course of the proceedings, popularly known as the ‘Bankia Case’, many other important pieces of evidence surfaced due to collaborative digital tools created by 15MpaRato activist platform XNet. Most pivotal of these were over 8000 emails from the ex-chairman of Caja Madrid, Miguel Blesa, which shed light on several malpractices and tax evasion by bankers and politicians amounting to over 15.5 million euros. As a result, in 2017, Spain’s High Court sentenced Rato and 64 other executives along with members of various political parties to varying terms of imprisonment. Unprecedentedly, all investors were able to recover the money they had lost in the scam.

Case Card

Name: Sala de lo Penal N °4/2017

Court: Supreme Court of Spain

Decision Date: 23 February 2017

Case Number: 59/2012, Juzgado Central de Instrucción n.º 4 en la Audiencia Nacional

Judgment: PDF

Issue: Spain’s High Court held 65 executives of Bankia, a leading Spanish bank and members of various political parties liable for fraud and administrative malpractices and appropriated varying terms of imprisonment for each.

Featured Actors

Simona Levi | Founder at XNet

Maddalena Falzoni | Founder at MaadiX

Emma Avilés Thurlow | Strategy and Communications Officer at Debt Observatory in Globalisation

Ruben Sáez | Scientist

Facts

Formation Of 15MpaRato

Spain was hit by a major financial crisis in 2008 which led to a recession, mass unemployment and the collapse of Spain’s property market. The effects of this crisis were felt for many years, with large companies facing bankruptcy and unemployment reaching a record rate of 32%. The devastating effects of the financial crisis led to massive protests in 2011. These protests were first staged on May 15 and later came to be known as the 15M or the Indignados movement. This movement saw Spaniards assembling in towns and city squares across Spain to show their distrust in the government and its handling of the financial crisis.

15MpaRato was created in May 2012, on the one-year anniversary of 15M. The group was driven by XNet, a non-profit activist organisation, and its objective was to put an end to economic and political impunity. The Bankia case was the first lawsuit launched by 15MpaRato, with XNet’s backing, to further this cause.

15MpaRato in itself was a witty wordplay where 15M stood for the Indignados movement and Rato held the dual meaning of Rato, the last name of Rodrigo Rato, and also meant ‘for a while’ in Spanish. The name made both intentions of the campaign clear. First, that the 15M movement was coming for Rato and others like him and second, that the 15M movement, which questioned the establishment, would remain ongoing for a while.

Facts Leading Up To The Lawsuit

In 2010, Rodrigo Rato joined Caja Madrid as its chairman. Prior to this, he held many other high-level positions, including Director of the International Monetary Fund, Minister of Economy, and Vice President of one of Spain’s major political parties, the People’s Party. The latter had envisioned him to be the future Prime Minister of Spain. At Caja Madrid, he was the successor of Miquel Blesa, who had held the position for 13 years.

Shortly after Rato’s joining, Caja Madrid became the largest of seven regional banks that consolidated to form ‘Bankia’. Subsequently, Rato became the President of Bankia. In 2011, Bankia listed itself on the stock exchange and carried out an Initial Public Offering (‘IPO’). Over 300,000 shareholders invested in Bankia for 3.75 euros per share and with this, the conglomerate was able to raise 3.2 billion euros.

In May 2012, Rato announced that Bankia had recorded profits upward of 300 million euros. Shortly after making this claim, Rato resigned from his post amid rumors regarding Bankia’s insolvency and, in June 2012, José Ignacio Gorigolzarri took over as the new president of Bankia.

In November 2012, within seven months of Rato’s announcement about its profit rates, Bankia announced that it was suffering a loss of 14 billion euros and was in urgent need of a bail-out. Share prices crashed to an all-time low of 0.01 euros. Bankia was considered key to the nation’s banking sector since it was the fourth-largest bank in Spain and held ten percent of Spain’s citizens’ total bank deposits. To avoid a collapse of the entire banking sector, the government stepped in and bailed out Bankia by partially nationalizing it. The 19 billion euro raised for the bailout was part of a larger debt that Spain had acquired from the European Union.

XNet analyzed the bailout plan and realized that a seventh of the amount was being used to rescue Bankia, a bank that was claiming profits of over 300 million euros only seven months ago. As collateral damage, Bankia’s 300,000 shareholders – mostly unemployed, elderly and families –had collectively lost over two billion euros due to Bankia’s sudden downfall. It was clear to the activists that a sudden need for a 19 billion euro bailout from the government and the steep fall of the share prices were extremely implausible unless there was maladministration and misrepresentation by the executive running Bankia. This led to the formation of 15MpaRato and the launching of the first lawsuit.

Even though the campaign was not against any one banker specifically, Rato was made its poster boy. This was because of the various positions he had held in government and the banking sector over the past decades, which symbolized the revolving door culture of the establishment, where high-level employees could easily switch between public sector and private sector jobs based on their personal connections.

In May 2012, 15MpaRato launched a campaign seeking any information from citizens that might help in holding Rato accountable. Within two weeks, hundreds of people had anonymously sent information that could potentially hold Rato liable for financial fraud.

The collected evidence made clear that the information provided to the public about Bankia’s financial situation at the time of the IPO was false and deceitful. This led to the launching of the first lawsuit against Bankia’s administration. Within the next year, the evidence collected enabled filing of two other cases against the bankers relating to the Preferred Shares Scam and the Black Card Scandal.

The First Lawsuit: The IPO Scam

In June 2012, 15MpaRato filed a lawsuit in Spain’s High Court against Rato and 32 other bankers on behalf of 14 aggrieved shareholders. This direct action was possible as the Spanish judicial system allowed the victims to be part of a trial. 15MpaRato was representing the victims. The group that they represented grew to 44. The main allegations made in the lawsuit related to negligent administration, financial misinformation, fraud and forgery. The lawsuit, led by the public prosecutor on behalf of the complainants, sought recovery of the money lost by the shareholders and imprisonment of the bankers.

In order to enable secure and anonymous evidence gathering, XNet created a digital tool in 2013 called XNet Leaks. The tool was inspired by Wikileaks, where any citizen could anonymously submit information about systemic corruption. Information submitted through XNet Leaks led to some groundbreaking revelations in the Bankia Case, such as the Black Card Scandal and Blesa’s emails which revealed the systematic corruption across the banking and political sectors and eventually led to two additional lawsuits.

The Second Lawsuit: The Preferred Shares Scam

The basis for the second lawsuit, filed in 2013, was evidence provided by Bankia’s own employees through XNet Leaks. It concerned an internal document titled “Sales pitch to sell preferred shares” and showed that 98% of shares sold to small savers and families were complex, high-risk shares. It was clear to 15MpaRato that the products were not put on the public market, but were sold only to specific, fragile targets. According to the documentation, employees were asked to keep shareholders under the false belief that the shares sold to them were fixed-income security shares, a less complex and more secure type of shareholding.

The leaked document encouraged the sale of these preferred shares to small savers and families lacking financial knowledge. Each page of the sales pitch had a recurring notice that stated, “This information should not be visible to customers.” Based on this evidence, 15MpaRato initiated another lawsuit against Bankia’s administration, alleging financial misinformation and criminal fraud. However, due to lack of conclusive proof, the court was unable to attribute guilt to any party and consequently, closed this case.

The Third Lawsuit: The Black Card Scandal

In December 2013, Xnet Leaks received an anonymous submission containing over 8,000 email exchanges from the account of Blesa, the former chairman of Caja Madrid. They included details of how executives of the bank and other influential political persons had access to a Visa Black Credit Card, which was paid off using Bankia’s savings account. Not only were Bankia’s funds being used for personal expenses of up to 50,000 euros per month, but all these expenditures were also being made without the knowledge of the tax agencies. This had led to over 15.5 million euros in tax evasion. Blesa’s emails were representative of Caja Madrid’s corrupt administration.

Due to the complexity and scale of the Black Card Scandal, the investigating magistrate and the prosecutor in the case, Judge Andreu, opened an adjoining lawsuit in 2016 against 65 bankers and politicians on charges of embezzlement and tax evasion. Rato and Blesa put up personal property amounting to 19 million euros in bail.

Outcome

In February 2017, Spain’s High Court sentenced Rato to four and a half years of imprisonment and Blesa to six years of imprisonment on account of embezzlement in the Black Card Scandal. 63 other bankers and politicians were also imprisoned for varying terms. Rato appealed the judgment and in October 2018, the Supreme Court upheld Rato’s conviction.

The first court case that was instituted by 15MpaRato against Bankia executives over the IPO scam and allegations of fraud, forgery and administrative malpractices remains pending in Spain’s High Court. However, in February 2016, in a separate judgement, the Supreme Court ordered Bankia to return money to two customers who were found to have been intentionally misled. To avoid the potential legal cost of over 400 million euros if all aggrieved shareholders went to court, Bankia announced that it would refund the lost money, amounting to over two billion euros, to all its shareholders along with four percent interest.

Collaboration

The main collaboration in this case took place between 15MpaRato and the citizenry at large. From the moment 15MpaRato called upon the public for any information that could potentially help imprison Rato, the narrative of the movement was clear: this was a movement by the people and for the people.

The 15MpaRato movement started with an anonymous message on the internet reading, “We will be catalysts. Countless small, surgical groups to free up living spaces…. We are not one, we are not ten, we are not a thousand or a million. We are countless and we are everywhere because we are the inhabitants of the world. The change is unstoppable, the change has already happened…. We have the power of the multitude organized in connected and inexpressible catalysts. With this – Let’s go for the Bankers.”

15MpaRato laid out a five-year plan to imprison Rato. The first of the three stages of the plan was to ensure that Rato was no longer seen as the future leader of Spain. As Simona Levi, founder of XNet and 15MpaRato mentions, “Delegitimizing Rato was our first goal because in corrupt countries like Spain, you cannot have a tribunal going against the future Prime Minister.” The second stage of the plan was ensuring that the citizens of Spain realized the extent of Bankia’s maladministration and condemned Rato for the same. This was done by sensitizing the community about the fraud committed and initiating a lawsuit against him and his colleagues, who were complicit in the crimes. The third stage was Rato’s imprisonment.

In May 2012, the first stage of the plan was initiated by calling upon citizens to submit any incriminating information that could potentially help imprison Rato. The evidence that 15MpaRato had anticipated would take one year to gather was collected within two weeks’ time.

The next obstacle was to overcome the financial burden for initiating the case. 15MpaRato saw this as an opportunity to host the first political crowdfunding campaign in Spain. Emma Avilés Thurlow, an activist and member of 15MpaRato recalled, “The anger and rebellion in people due to the 15M movement helped us activate citizen enthusiasm for 15MpaRato.” This was possibly the reason that over 11,000 people tried to donate money within the first hour of the platform going live, leading to a system shutdown. 15MpaRato also created a digital tool to accommodate secure crowdfunding in the future.

The organisation shared spending accounts of the money received on its website. This created trust and transparency between the public and 15MpaRato. It was also a reliable way to refute claims of money-making that were often alleged by members of the press against 15MpaRato.

Ever since the first lawsuit was filed in June 2012, the campaign was carried out on two fronts: internal and external. The internal group focused on developing the overall strategy and the external group, comprising the citizens that were a part of the digital platforms, stepped forward to help advance the campaign.

The internal group was a core group of 20 activists led by Levi. She described the internal group as an “agile guerrilla group where everybody was clear of the role they would play in the plan.” Ruben Sáez, a scientist by profession, was part of this internal group. He recalls how each member of the group used their strength to help attain the campaign’s objective. “Maddalena Falzoni used her expertise in tech to create and maintain the technical tools for the campaign. Emma Avilés Thurlow was in charge of networking and outreach. Sergio Salgado, a communication and network expert, used to write on 15MpaRato’s blog to communicate the feelings of empowerment amongst the citizens. Pau López, a graphic designer, helped in designing memes and images.”

The campaign’s internal group maintained anonymity for the majority of the campaign and used only their collective name, 15MpaRato. This was for three reasons. Firstly, they didn’t want the government to identify and obstruct individual members. Secondly, they didn’t want the government to be able to assess the number of people involved in the movement. As Levi mentions, “We didn’t want the establishment to know whether we were one or one thousand in number.” Lastly, since the group comprised of majority female and LGBTQ members, in Levi’s words, “we couldn’t come out in public because then, we would perhaps not be taken seriously.” However, some group members disclosed their names to take credit for the movement amid the ongoing trials and due to this, the whole group eventually shared their names with the press.

The external group, which comprised the citizenry at large, was created by 15MpaRato using digital tools such as social media platforms and mailing lists. These platforms were created so that the citizens could interact and engage with the movement. Levi recalled that during the campaign, the internet was the best place for collaboration. “If we wanted to check the accountability of a bank, we would go on Twitter and write ‘Hey guys, we have to check this balance sheet. Who is good at it?’ If we couldn’t find a certain legal article, we’d go online and say, ‘Can you help us?’.” In this manner, hundreds of thousands of citizens were mobilized at different stages of the case for both crowdfunding and evidence gathering.

The XNet Leaks tool was a byproduct of this digital collaboration. It was an online portal that allowed citizens to anonymously submit evidence against Bankia and led to breakthroughs such as the leaked Blesa emails. Maddalena Falzoni, the founder of MaadiX, a free platform for secure tools, was the technologist behind the creation of XNet Leaks – based on Globaleaks – and other digital tools in the campaign. She stated, “As an activist group, we were concerned about citizens’ privacy and security and so we decided set up XNet Leaks, which was a free and secure channel for anonymous communication.”

15MpaRato put all relevant evidence of the Bankia case on their website to enable other aggrieved parties to file separate lawsuits. Even today, XNet Leaks continues to be a platform where any evidence of corruption can be submitted and, if credible, taken forward by 15MpaRato and XNet. This is in line with Falzoni’s collaborative spirit in stating that:

“Technology must be at the service of human rights defenders and people in general. It must not turn itself into a layer of complexity over all the other things we have to do.”

This historic movement led to 300,000 small savers getting justice by holding the corrupt bankers who defrauded them liable and getting their lost money back. This was possible because of solid partnerships between activists and innumerable citizens who mobilized to fight for transparency and accountability. The movement also reaffirmed the importance of keeping civil society empowered. As Levi encapsulates the essence of 15MpaRato, “When civil society is criticizing the establishment and the establishment’s response is ‘I don’t care’, it is very important for civil society to say ‘Okay, then we will show you’.”

Lessons Learned

The Bankia case’s outcome was possible primarily because of collaboration between the tight-knit community 15MpaRato had built through campaigning and mass mobilization of the citizenry. The case is also a lesson in converting obstacles into opportunities.

Even though the campaign exhibited its strength in numbers, Levi admitted that in lengthy trials such as this one, collaboration only happens in phases. She stated, “Something very important you must know is that many times you will be alone. You will gather people only for a very short part of the way. So sometimes, you will be many people but most times you will be very few. You cannot expect people to stay for such a long time with the same level of participation.” Even so, the team takes a lot of pride in the fact that 12 of the original 20 members who started 15MpaRato continue working together on similar campaigns.

Another lesson that the team learned mid-way through the campaign was that communicating to citizens and telling them that the case was initiated and followed through by ordinary citizens was much harder than the act of actually instituting the case against the bankers. The members of 15MpaRato partially attributed this to the Spanish government and press, which they felt was motivated to retain power and tried to discourage citizen empowerment. This could also be the reason why the media attributed credit for the Bankia case to political parties, journalists and lawyers. However, as Levi mentioned, “Before the launch of the campaign, no political party was willing to help with concrete solutions. Neither were news organisations willing to join the dots about the scam.” Hence, it was very important to the team that citizens got to know that non-legal and non-economic ordinary citizens were behind the case.

XNet did so by writing a book and showcasing a play across several cities of Spain to accurately depict how the incidents leading up to the scam unfolded and how it was the ordinary citizens of Spain who had led this incredible victory. Levi, who is also a playwriter and theatre director, wrote and directed the play. She stated: “We did the play and wrote the book to share credit with citizens at large. It was an important element of 15MpaRato to prove that the public sector and citizens must collaborate and organize to create a healthy democracy.”

The movement also faced a lot of resistance from the public prosecutor. Though the prosecutor was required to prosecute the bankers, in Levi’s opinion, “He thought of the complainants as anti-establishment and took it upon himself to protect the bankers.” She recalls, “When we were presenting evidence, the first one saying that it was not good was usually not the defence, it was the prosecutor.” Each banker being prosecuted also had a giant legal team that tried to exhaust 15MpaRato’s internal group by sending them hundreds of pages of reports every day. This is when the team capitalized on the vast community that had been mobilized by asking for assistance online.

Additionally, the press was not very helpful in the early stages of the case and refused to cover the Bankia case. Rato’s wife was one of the directors of El País, a leading national daily newspaper in Spain, and the mainstream press often changed the narrative of the story, not showcasing how citizens were at the helm of this movement. However, this changed once the movement gained traction in the country, especially after the Blesa email leak.

Reiterating a line from the play staged across Spain, “This is the story of how government elites plundered the county. But it is also the story of how citizens got together and brought to light the truth. And how normal, ordinary people, joining forces, learning and explaining how things really happened, are changing the usual ending.”